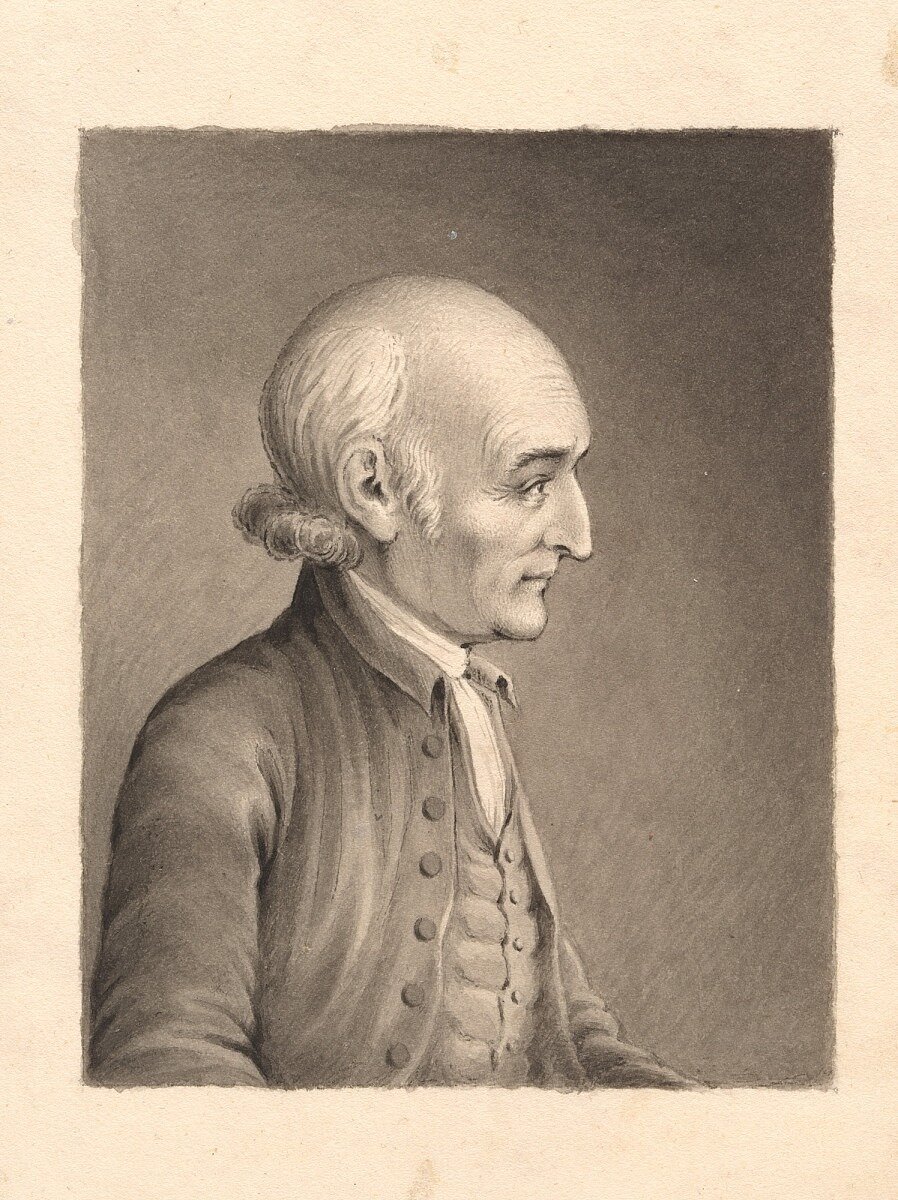

George Wythe

Virginia

George Wythe was born in 1726 on the family plantation, Chesterville, in Elisabeth County (now Hampton), Virginia. His father, Thomas Wythe, died when he was three. He was educated early on by his well-educated mother, Margaret Walker Wythe. She taught him Latin and Greek. Also, she included in his education: the classics, logic, and science. At 14 years of age, he began attending a grammar school at William & Mary College. Later, he read law under the supervision of his uncle, Stephen Dewey. At 20 years of age, he sat for examination with his uncle, Mr. Dewey and Peyton Rudolph, a future president of the Continental Congress. He was admitted to the bar in Spotsylvania County.

While working in the county, George Wythe lived with the king’s attorney, Zachary Lewis. He became enamored with his daughter, Ann, and wed her on December 26, 1747. Their marriage was tragically cut short when Ann contracted a fever seven months later and died. According to his account, he sought solace in many a Spotsylvania inn. The following year he moved to Williamsburg and worked with his late wife’s uncle, Benjamin Waller.

In the same year, Mr. Wythe entered public service as he was appointed clerk of two House of Burgesses’ committees, the Privileges and Elections Committee, and the Propositions and Grievances Committee. In 1754, his legal reputation and work earned him an appointment by the royal governor to be the king’s attorney (attorney general) for the colony. The next year, the death of a representative in the House of Burgesses prompted his selection to the governing body. Tragedy, once again, visited him when his brother died in 1755. As a consequence, he inherited the family estate.

In 1758, Francis Fauquier replaced Robert Dinwiddie as royal governor. In light of living near George Wythe, Governor Fauquier and Mr. Wythe became good friends along with Professor William Small of William & Mary College. In time, Professor Small brought along a bright student of his, Thomas Jefferson. The four of them discussed science, literature, architecture, politics, and morals. At the suggestion of Professor Small, Mr. Wythe tutored young Jefferson. He lived with Mr. Wythe for five years and recalled those evenings at the governor’s palace with much fondness. He said they were nights of “more good sense, more rational and philosophical conversations, than in my life beside.” The two would remain friends for the remainder of Wythe’s life.

Mr. Wythe began battling Britain’s meddling in colonial affairs in 1763. The first instance involved Virginia’s law, Two Penny Act, which stabilized the salary of Anglican ministers who were paid in tobacco. The act provided for ministers when the annual yield of tobacco was low, but it prevented ministers from receiving a noticeably higher annual wage when there was a larger yield. The law brought predictability to the situation. The clergy did not approve and appealed to the authorities in England and they overturned the law. Mr. Wythe and Patrick Henry argued against the British government’s involvement. Mr. Henry stated, “that a King by annulling or disallowing acts of so salutary a nature, from being Father of his people degenerated into a Tyrant, and forfeits all right to his subjects’ obedience.”

The heat of Mr. Henry’s statement continued into 1764 when the Stamp Act was passed by Parliament. George Wythe wrote a letter of scathing admonition that had to be edited by his colleagues due to its stridency. Part of the final version stated the House of Burgesses “conceive it is essential to British liberty, the laws imposing taxes on people, ought not to be made without the consent of representatives chosen by themselves.” He was one of the first colonial leaders to suggest the colonies separate themselves from England.

Mr. Wythe also had significant issue with the crown’s governor. In 1768, he became mayor of Williamsburg. He and Governor John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, regularly collided as the governor strove to govern by himself apart from the House. Lord Dunmore, several times, took it upon himself to postpone or convene the House of Burgesses. The tension apexed when the English government closed the Boston port due to the tea party. The House of Burgesses set aside a day for prayer and fasting regarding the situation on June 1st. Lord Dunmore, none too pleased, dissolved the governing body. It assembled at a nearby tavern and selected men to represent Virginia at the First Continental Congress.

George Wythe served as a Continental Congress delegate in 1775-76, but he was often engaged in state affairs. He assisted in drafting the Virginia constitution and designing the state seal. The constitution declared Virginia would cease to be a colony of the crown and become an independent state. He was not even present on August 2nd to sign of the Declaration of Independence. He would sign it at a later date.

Later in the year 1776, Messrs. Wythe, Jefferson, and Edmund Pendleton embarked on a three-year project of revising Virginia’s legal code. Mr. Wythe also was speaker of the House of Delegates and a judge for the high court of chancery. His service on the high court for 28 years provided him the privilege of shaping the state’s jurisprudence.

George Wythe also shaped the minds of the state’s most preeminent lawyers and political leaders by being named the first professor of William & Mary’s law school. Some of his most well-known students include Henry Clay, James Monroe, and John Marshall. In testament to his great intellect, Mr. Marshall only received six weeks of legal training from the professor. He would go on to become the longest serving chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He is regarded as one of the most influential jurists to serve on the high court.

Following the war and in addition to his state duties, Mr. Wythe engaged much in transforming the Articles of Confederation into a constitution. He was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. His time was cut short though due to his wife’s illness that took her life in August.

George Wythe’s death was also caused by illness but not from a natural source such as bacteria or viruses. It came from arsenic, which came from the hand of his great nephew, George Wythe Sweeney. Mr. Sweeney had come to live with his great uncle and in 1803, Mr. Wythe had a will drafted bequeathing much of his wealth to his great nephew upon his death. Unfortunately, Mr. Sweeney began stealing from his great uncle and Mr. Wythe became aware of his ungrateful acts. Consequently, he amended his will giving a portion of the apportionment to Mr. Sweeney to his freed slave, Michael Brown. Under unknown circumstances, Mr. Sweeney found out about the changes his great uncle made to his will.

Not pleased whatsoever, the great nephew poisoned his great uncle and Mr. Brown. Mr. Wythe did not die immediately. He remained alive for 14 days and during that period he wrote his great nephew completely out of his will. Mr. Brown died a few days after being poisoned.

On June 8, 1806, one of the nation’s founding fathers and one of the foremost legal minds of the 18th century, George Wythe, died at the hand of a relative. He lived to be 80 years of age.